22. Kernel Support Vector Machine

Kernel SVM

Introduction

The soft margin approach solved the problem of imperfectly classified or noisy data; however, it is still limited to linear classification (with a decision boundary in the form $Ax + b = 0$). For non-linearly separable data, the soft margin approach will also fail immediately.

The figure below shows the failure of the soft margin approach in a case of non-linearly separable data.

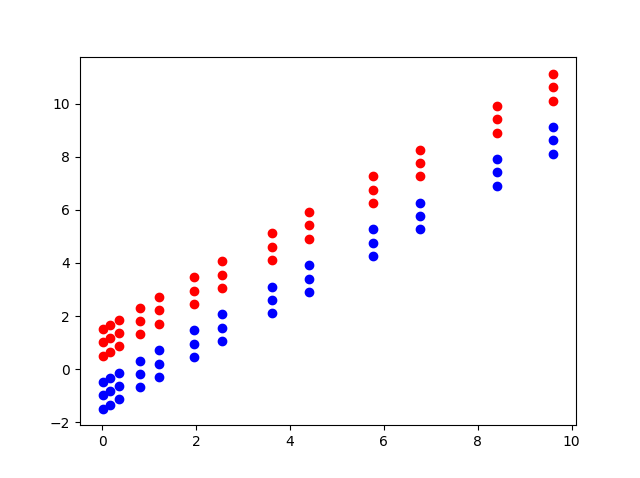

However, if we transform this data into a new space from $(x_1, x_2)$ to $(x_1^2, x_2)$, the data transforms as follows:

We can see that the data can now be classified linearly. We only need to apply the soft margin approach or other linear classification methods to this transformed data.

The problem has been solved, but how do we know that transforming the space from $(x_1, x_2)$ to $(x_1^2, x_2)$ makes the data linearly separable? By plotting the data, we can observe that it can be separated by a parabolic curve, which is why we use that new space. However, for other problems where the data forms a complex curve or involves more than three dimensions, can we still manually determine the right space transformation? This approach of visualizing data is known as data visualization, a technique currently being developed in data science. While there are visualization methods that can help us understand the data and find appropriate methods for solving problems, not all data can be visualized easily, making this a developing field. For complex data, visualizing and manually determining the transformation may not be feasible. Fortunately, there is another approach: the use of kernels.

With this idea, we transform the original space into a new one using the function $\Phi(x)$. In the example above, $\Phi(x) = [x_1^2, x_2]^T$.

In the new space, the problem becomes:

\[\begin{aligned} \lambda^{*} &=& \arg\max_{\lambda} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \lambda_i - \dfrac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} \lambda_i \lambda_j y_i y_j \Phi(x_i)^T \Phi(x_j) \nonumber \\ \text{subject to: } && \sum_{i=1}^{N} \lambda_i y_i = 0 \nonumber \\ && 0 \leq \lambda_i \leq C, \quad \forall i = 1, 2, \dots, N \nonumber \end{aligned}\]The decision function in the transformed space is:

\[\begin{aligned} f(\Phi(x)) &=& w^T \Phi(x) + b \nonumber \\ &=& \sum_{m \in S} \lambda_m y_m \Phi(x_m)^T \Phi(x) + \dfrac{1}{N_M} \sum_{n \in M} \left( y_n - \sum_{m \in S} \lambda_m y_m \Phi(x_m)^T \Phi(x_n) \right) \nonumber \end{aligned}\]Calculating $\Phi(x)$ directly is very difficult, and $\Phi(x)$ may have a very large number of dimensions. Observing the above expressions, instead of calculating $\Phi(x)$, we only need to calculate $\Phi(x)^T \Phi(z)$ for any two points $x, z$.

This technique is called the kernel trick. Methods that use this technique are known as kernel methods.

Define the kernel function as $k(x, z) = \Phi(x)^T \Phi(z)$. We can rewrite the problem as:

\[\begin{aligned} \lambda^{*} &=& \arg\max_{\lambda} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \lambda_i - \dfrac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{N} \sum_{j=1}^{N} \lambda_i \lambda_j y_i y_j k(x_i, x_j)v \nonumber \\ \text{subject to: } && \sum_{i=1}^{N} \lambda_i y_i = 0 \nonumber \\ && 0 \leq \lambda_i \leq C, \quad \forall i = 1, 2, \dots, N \nonumber \end{aligned}\]The decision function becomes:

\[\begin{aligned} f(\Phi(x)) &=& w^T \Phi(x) + b \\ &=& \sum_{m \in S} \lambda_m y_m k(x_m, x) + \dfrac{1}{N_M} \sum_{n \in M} \left( y_n - \sum_{m \in S} \lambda_m y_m k(x_m, x_n) \right) \end{aligned}\]Mathematical Analysis

Recall the dual problem for the soft margin SVM with data that is almost linearly separable:

\[\begin{aligned} \lambda &=& \arg \max_{\lambda} \sum_{n=1}^N \lambda_n - \dfrac{1}{2} \sum_{n=1}^N\sum_{m=1}^N \lambda_n \lambda_m y_n y_m \mathbf{x}_n^T \mathbf{x}_m \nonumber \\ \text{subject to:}~ && \sum_{n=1}^N \lambda_n y_n = 0 \label{eq:kernel1}\\ && 0 \leq \lambda_n \leq C, ~\forall n= 1, 2, \dots, N \nonumber \end{aligned}\]where:

-

$N$: Number of data pairs in the training set.

-

$\mathbf{x}_n$: Feature vector of the $n^{th}$ data in the training set.

-

$y_n$: Label of the $n^{th}$ data, equal to 1 or -1.

-

$\lambda_n$: Lagrange multiplier corresponding to the $n^{th}$ data point.

-

$C$: A positive constant that balances the size of the margin and the compromise of data points in the unsafe region. When $C = \infty$ or is very large, the soft margin SVM becomes a hard margin SVM.

After solving for $\lambda$ in $\eqref{eq:kernel1}$, the label of a new data point is determined by the sign of:

\[\sum_{m \in \mathcal{S}} \lambda_m y_m \mathbf{x}_m^T \mathbf{x} + \dfrac{1}{N_{\mathcal{M}}} \sum_{n \in \mathcal{M}} \left( y_n - \sum_{m \in \mathcal{S}} \lambda_m y_m \mathbf{x}_m^T \mathbf{x}_n \right) \label{eq:kernel2}\]where:

-

$\mathcal{M} = {n: 0 < \lambda_n < C}$ is the set of points on the margin.

-

$\mathcal{S} = {n: 0 < \lambda_n}$ is the set of support points.

-

$N_{\mathcal{M}}$ is the number of elements in $\mathcal{M}$.

With real-world data, it is difficult to have data that is almost linearly separable, so the solution to $\eqref{eq:kernel1}$ may not produce a good classifier. Suppose we can find a function $\Phi()$ such that after transforming to the new space, each data point $\mathbf{x}$ becomes $\Phi(\mathbf{x})$, and in this new space, the data is almost linearly separable. In this case, the hope is that the solution to the soft margin SVM will provide a better classifier.

In the new space, $\eqref{eq:kernel1}$ becomes:

\[\begin{aligned} \lambda &=& \arg \max_{\lambda} \sum_{n=1}^N \lambda_n - \dfrac{1}{2} \sum_{n=1}^N\sum_{m=1}^N \lambda_n \lambda_m y_n y_m \Phi(\mathbf{x}_n)^T \Phi(\mathbf{x}_m) \nonumber \\ \text{subject to:}~ && \sum_{n=1}^N \lambda_n y_n = 0 \label{eq:kernel3} \\ && 0 \leq \lambda_n \leq C, ~\forall n= 1, 2, \dots, N \nonumber \end{aligned}\]The label of a new data point is determined by: \(\begin{aligned} \mathbf{w}^T\Phi(\mathbf{x}) + b = \sum_{m \in \mathcal{S}} \lambda_m y_m \Phi(\mathbf{x}_m)^T \Phi(\mathbf{x}) + \dfrac{1}{N_{\mathcal{M}}} \sum_{n \in \mathcal{M}} \left( y_n - \sum_{m \in \mathcal{S}} \lambda_m y_m \Phi(\mathbf{x}_m)^T \Phi(\mathbf{x}_n) \right) \label{eq:kernel4} \end{aligned}\)

As mentioned above, calculating $\Phi(\mathbf{x})$ directly for each data point may require a lot of memory and time because the dimensionality of $\Phi(\mathbf{x})$ is often very large, possibly even infinite! Moreover, to determine the label of a new data point $\mathbf{x}$, we need to transform it to $\Phi(\mathbf{x})$ in the new space and then take the dot product with all $\Phi(\mathbf{x}_m)$, where $m$ is in the set of support points. To avoid this, we can use the following interesting observation.

In problem $\eqref{eq:kernel3}$ and expression $\eqref{eq:kernel4}$, we do not need to calculate $\Phi(\mathbf{x})$ directly for every data point. We only need to calculate $\Phi(\mathbf{x})^T \Phi(\mathbf{z})$ for any two data points $\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{z}$. This technique is known as the kernel trick. Methods that use this technique—calculating the dot product of two points in the new space instead of their individual coordinates—are collectively known as kernel methods.

Now, by defining the kernel function $k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{z}) = \Phi(\mathbf{x})^T \Phi(\mathbf{z})$, we can rewrite problem $\eqref{eq:kernel3}$ and expression $\eqref{eq:kernel4}$ as follows:

\[\begin{aligned} \lambda &=& \arg \max_{\lambda} \sum_{n=1}^N \lambda_n - \dfrac{1}{2} \sum_{n=1}^N\sum_{m=1}^N \lambda_n \lambda_m y_n y_m k(\mathbf{x}_n, \mathbf{x}_m) \nonumber \\ \text{subject to:}~ && \sum_{n=1}^N \lambda_n y_n = 0 \label{eq:kernel5} \\ && 0 \leq \lambda_n \leq C, ~\forall n= 1, 2, \dots, N \nonumber \end{aligned}\]And:

\[\sum_{m \in \mathcal{S}} \lambda_m y_m k(\mathbf{x}_m, \mathbf{x}) + \dfrac{1}{N_{\mathcal{M}}} \sum_{n \in \mathcal{M}} \left( y_n - \sum_{m \in \mathcal{S}} \lambda_m y_m k(\mathbf{x}_m, \mathbf{x}_n) \right) \label{eq:kernel6}\]Example: Consider transforming a data point in two dimensions $\mathbf{x} = [x_1, x_2]^T$ into a point in five dimensions $\Phi(\mathbf{x}) = [1, \sqrt{2} x_1, \sqrt{2} x_2, x_1^2, \sqrt{2} x_1 x_2, x_2^2]^T$. We have:

\[\begin{aligned} \Phi(\mathbf{x})^T\Phi(\mathbf{z}) &=& [1, \sqrt{2} x_1, \sqrt{2} x_2, x_1^2, \sqrt{2} x_1 x_2, x_2^2] [1, \sqrt{2} z_1, \sqrt{2} z_2, z_1^2, \sqrt{2} z_1 z_2, z_2^2]^T \nonumber \\ &=& 1 + 2 x_1 z_1 + 2 x_2 z_2 + x_1^2 z_1^2 + 2 x_1 x_2 z_1 z_2 + x_2^2 z_2^2 \nonumber \\ &=& (1 + x_1 z_1 + x_2 z_2)^2 = (1 + \mathbf{x}^T \mathbf{z})^2 = k(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{z}) \nonumber \end{aligned}\]In this example, it is clearly easier to calculate the kernel function $k()$ for two data points than to compute each $\Phi()$ and then multiply them together.

Properties of the Kernel Function

The kernel function must satisfy Mercer’s theorem:

Given a set of data points $x_1, \dots, x_n$ and any set of real numbers $\lambda_1, \dots, \lambda_n$, the kernel function $K()$ must satisfy:

\[\sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^n \lambda_i \lambda_j K(x_i, x_j) \geq 0\]This means that the kernel function must be convex.

In practice, some kernel functions that do not strictly satisfy Mercer’s theorem are still used because the results are acceptable.

Common Kernel Functions

In practice, the following kernel functions are commonly used:

-

Linear: $k(x, z) = x^T z$

-

Polynomial: $k(x, z) = (r + \lambda x^T z)^d$ where $d$ is a positive integer indicating the degree of the polynomial.

-

Radial Basis Function (RBF): $k(x, z) = \exp(-\lambda |x - z|_2^2), \quad \lambda > 0$

-

Sigmoid: $k(x, z) = \tanh(r + \lambda x^T z)$

In addition to the commonly used kernels above, there are many other kernels, such as string kernel, chi-square kernel, histogram intersection kernel, etc.

The effectiveness of different kernels is a topic of extensive research, but RBF (Gaussian kernel) is the most commonly used.

Andrew Ng has a few tricks for choosing kernels:

-

Use a linear kernel (or logistic regression) when the number of features is larger than the number of observations (number of training examples).

-

Use a Gaussian kernel when the number of observations is larger than the number of features.

-

If the number of observations is larger than 50000, speed could be an issue when using the Gaussian kernel, so a linear kernel might be preferable.

Neural networks can handle all of these cases (and do well), but they may be slower. Another note: neural networks use convex optimization.

Summary

| Neural Networks | SVM | General Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| PLA | Hard Margin SVM | Two classes are linearly separable |

| Logistic Regression | Soft Margin SVM | Two classes are almost linearly separable |

| Softmax Regression | Multi-class SVM | Multi-class classification problem (linear boundaries) |

| Multi-layer Perceptron | Kernel SVM | Data is not linearly separable |